People have committed crimes against each other since the beginning of time. Some crimes are solved — others aren’t. Occasionally, disappearances have no clues of maleficence, leaving unsolved mysteries in Pierce County for years or decades with an eternity of questions.

That fact doesn’t stop the search for answers. The advent of online databases and social media, as well as the medical advancements in DNA profiling, have given new hope to families and law enforcement agencies that missing person and unsolved murder cases can one day be solved.

One of the oldest unsolved murders historical researchers have rekindled efforts to solve involves the murder of Nisqually Chief Quiemuth in the fall of 1856. The Indian Wars had just ended, and Territorial Gov. Isaac Stevens wanted revenge. Quiemuth had just surrendered after his half-brother Chief Leschi was betrayed and captured to face trial for murder in Steilacoom for allegedly participating in an ambush earlier in the hostilities. Quiemuth arrived at the governor’s home in the early hours of November 19. He and some white settlers bedded down to get a few hours of sleep before the planned escort to Steilacoom.

“All was quiet, the room was dimly lighted, when suddenly he was shot …” the newspaper, Pioneer Democrat wrote at the time. “Much confusion ensued — all rushed to the door, Quiemuth included, where he was mortally stabbed, and expired almost instantly.”

The attackers escaped. Suspicious eyes immediately turned to Joseph Burton, a son in law of a man Quiemuth had reportedly killed during the war. Burton was seen in the room before the attack but witnesses wouldn’t, or couldn’t, positively identify him after his arrest. He was later released and the case went unsolved. But Quiemuth has not been forgotten. The highest point in Thurston County bears his name. Quiemuth Peak became official in 1993, while historians continue to solve the mystery of his murder.

Another unsolved murder is the case of Charles Mattson, a Tacoma ten-year-old who was kidnapped at gunpoint from his parents’ home along North Verde Street in December of 1936. A ransom note wanted $28,000 for his safe return. It was the era of high-profile kidnappings. Charles’ parents, Dr. and Mrs. William W. Mattson, were unusual targets for a ransom demand since they had lost much of their savings in the Depression and their $50,000 home was heavily mortgaged. The boy’s battered body was found in the woods in Snohomish County on January 10, 1937. His death brought the largest manhunt in Pacific Northwest history, involving FBI agents as well as state, county and city law officers. After a few weeks, despite questioning many suspects, all leads failed. The investigation centered on the theory the kidnapper was insane. Police arrested one man, Frank Olson, who later confessed. But it was eventually learned Olson was an escaped patient from a mental facility who liked to pose as famous criminals. The case remains unsolved.

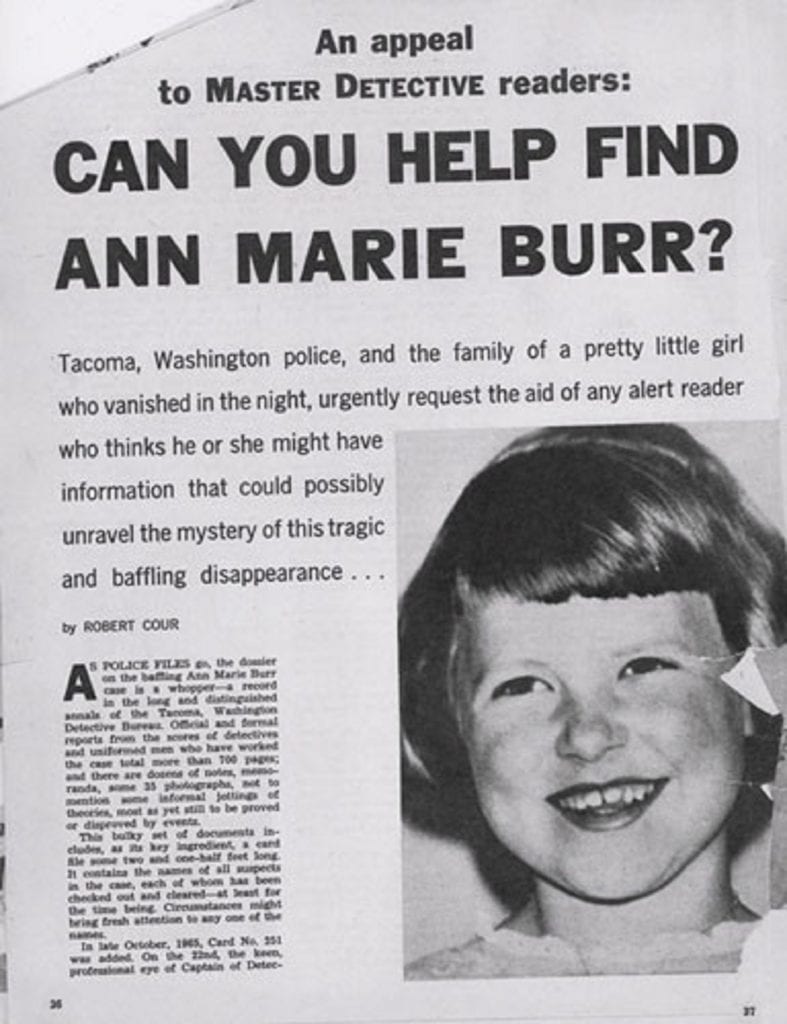

Yet another unresolved case is that of Ann Marie Burr. During the night of August 31, 1961, eight-year-old Burr went missing from her bedroom at the corner of North 14th and North Junett. The front door had been locked, but the next morning it was found to be open. On the porch was a small men’s shoe print. There is speculation Burr was the first victim of serial killer Ted Bundy, who lived just a few blocks away and was 14 at the time. While he denied killing Burr until he was executed in Florida in 1989, he had already confessed to killing 36 women. There were only four homicides in the city that year. The three others were solved. Bundy most certainly knew Burr from his time in the neighborhood and admitted he killed squirrels, cats and dogs in the area from as young as six. Coincidences, however, don’t prove guilt, so that case is likely to remain a mystery.

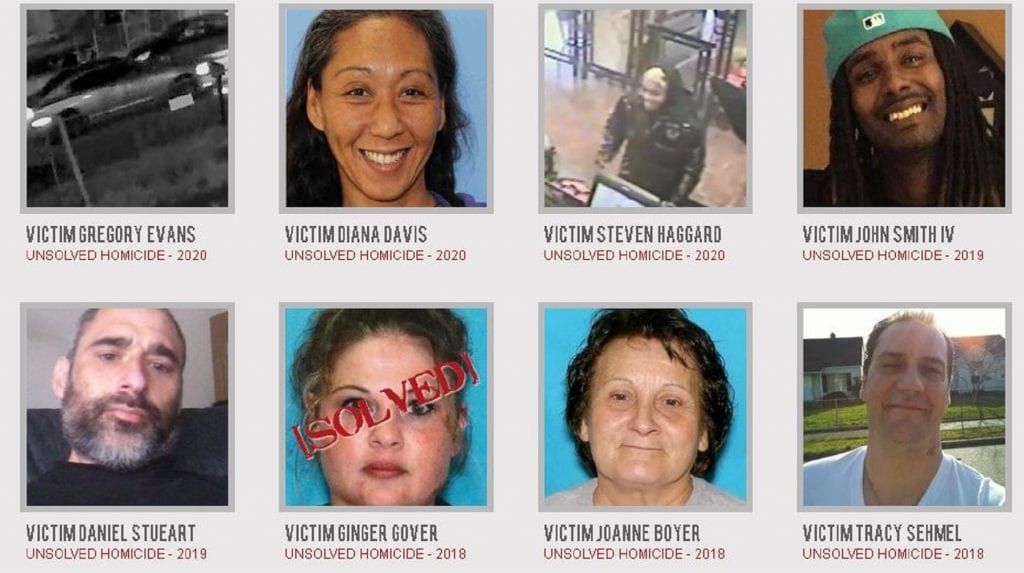

Of course, unsolved murders and unexplained disappearances aren’t just subjects for historical research. Crimes continue to go unsolved. Questions remain members of the public might be able to answer. The rise of the internet allows the widespread distribution of information about unsolved murders and missing people under the idea that someone knows something about the mysteries. In 2012, Crime Stoppers of Tacoma-Pierce County launched a database of unsolved murders with hundreds of cold case profiles dating back to 1995. After sitting on shelves for decades, older cases from the Pierce County Sheriff and the Tacoma Police Department are also being added as are new unsolved murders after they occur.

The most recent entry is that of the murder of Gregory Evans, a 55-year-old man who was shot to death while he stood with an acquaintance next to their cars on East 60th Street on November 27, 2020.

“The victims were standing by their vehicles when a silver or gray Dodge Charger drove by at a slow rate of speed,” according to Crime Stoppers. “The occupants of the Charger fired multiple rounds at the victims before driving away. Evans died at the scene as a result of his wounds, and his acquaintance was seriously injured.”

Another notable cold case includes that of Billy Shirley III. The 17-year-old boy from East Tacoma was shot and killed at 5:00 a.m. on August 27, 2011, after he drove to pick up friends at a party in a warehouse along Center Street. An argument led to gunfire witnessed by more than 100 people, yet no one has identified the shooter. His mother, Shalisa Hayes, has since founded the Billy Shirley III Foundation that championed the creation of the Eastside Community Center.

A strange case, one not on the official list, is the double murder of Michael A. Johnston and Rochelle L. Robinson. They were killed on June 27, 1994, in South Tacoma. Johnston was a 25-year-old, married father of two and Robinson was a 19-year-old woman studying to become a teacher. They were having an affair. They had spent the evening playing cards only to be found dead the following morning. Johnson laid dead by Robinson’s car with a gunshot wound to his head and his throat slashed. Robinson’s body was found five miles away under a cardboard box. She had been stabbed and slashed with a knife and was found wearing Johnson’s t-shirt inside out.

A friend of hers told police Robinson had been stalked by an unidentified man during the three months prior. The prevailing theory is the double murder was a crime of passion perpetrated by that unknown stalker. But little is known. Few clues came even after it was profiled on the television show, Unsolved Mysteries in 1996. Fans of the show have compiled thousands of case summaries of unsolved murders and disappearances, including a roster of strange cases in this area in hopes the crowd-brain of the internet can finally bring closure to the victim’s loved ones.

That closure came for the families of two Tacoma girls who were murdered back in 1986. Michella Welch was a 12-year-old girl who had taken her younger sisters to Puget Park only to return home to get their lunches. The younger girls stayed behind to play and then went to a nearby business to use the restroom. While they were away, Welsh apparently returned. She was last seen alive talking to an unidentified man. Her body was found in a neighborhood gulch around midnight. Her throat was cut. Just months later, 13-year-old Jennifer Marie Bastian disappeared while biking around Point Defiance. Her body was found in the woods a month later. She had been strangled.

Tacoma police finally solved both cases in mid-2018, after DNA investigators used a genetic genealogical site to narrow their list of suspects by creating “family trees.” They compared the suspects’ DNA with genetic samples customers of the website provide to determine genetic lineages. That process determined Welch was reportedly killed by Gary C. Hartman, and Bastian was killed by Robert D. Washburn. Hartman awaits trial and is being held at Pierce County Jail on a $5 million bond. Washburn has since pled guilty and received a 26-year sentence in 2019.

Another cold case with promising leads is the disappearance of Teekah Lewis. The two-year-old girl was abducted from what was then the New Frontier Bowling Alley off Center Street in 1999. She was playing in the arcade when she vanished. The bowling alley was locked down and police arrived moments later, but she was never seen again. Her mother holds a vigil at the site every year since, hoping Lewis is found. Last year’s vigil came with the news that police had interest in a man who was at the bowling alley at the time and has since been unable to be located. After two decades since her disappearance, any news that the case is still being investigated is good news.