During World War I, Germany was the enemy. Across America, many saw German Americans as their enemy, too. Even here in Tacoma, people turned against their neighbors, viewing everything German with suspicion.

Germans in Washington

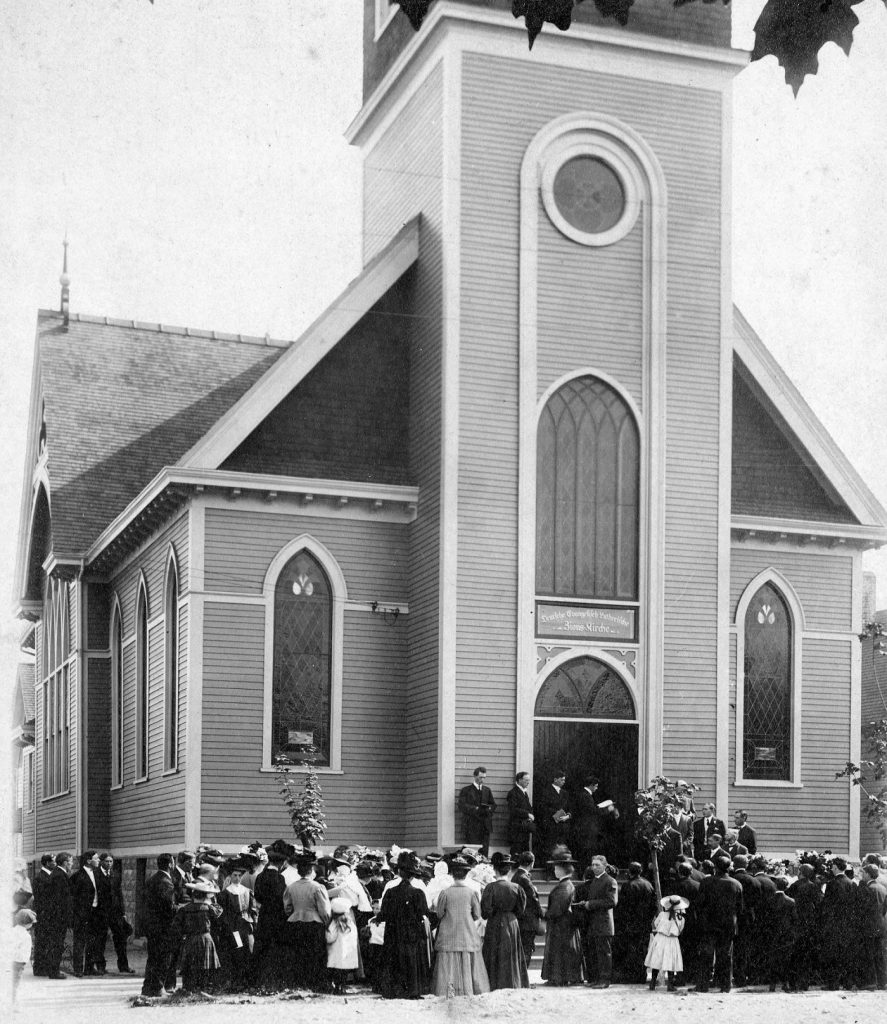

This attitude would have shocked many of Washington’s earliest settlers. German immigrants and their descendants had long been one the largest ethnic groups in the region.

When World War I broke out in August 1914, it seemed unlikely that America would become involved. That same month, hundreds of Germans from Tacoma and Pierce County gathered at Fraternity Hall for a patriotic rally. They urged American neutrality and pledged to support relief efforts for German/Austrian soldiers and civilians. They held several fundraisers over the next few years.

War!

But when America entered the war on the side of the Allies on April 6, 1917, everything changed. Germany was the enemy now, and in the eyes of many, that made all German Americans suspect. Non-citizen Germans were required to register as “enemy aliens.”

While no Tacoma Germans were arrested for spying, Dr. John Reitz was arrested in March 1918 and “interned” for the rest of the war. He was not accused of spying but of celebrating the deaths of women and children on the Lusitania, sunk by a German submarine. The father of three young children (and a German army veteran), the insurance company medical examiner denied the accusations. People had been harassing him, Reitz said, for his earlier support of Germany. He just wanted to be left alone.

Sprechen Sie Deutsch?

Everything German became suspect. Bands stopped playing German music. Sauerkraut was called “Liberty cabbage.” But the biggest flashpoint was language.

Prior to the war, German was the most popular foreign language at Washington high schools. Now, textbooks and teachers were under scrutiny. Two hundred students were taking German at Tacoma’s two high schools when classes began in September 1917, a slight decrease from the year before. “We have a large beginners’ class,” a Stadium High School teacher told the Tacoma Times on September 20, 1917, “and they are all enthusiastic.”

But these students were not ready for the firestorm of controversy they would face. That same month, the textbook “Im Vaterland” (In the Fatherland) by Paul Valentine Bacon had become the focus of a national scandal over “pro-German” propaganda because of its brief praise of the Kaiser. Stadium had already dropped the book. Now Lincoln High School would as well.

But German began to be seen as an evil language. Tacoma newspapers published frequent editorials against using German and demanding immigrants “speak English.”

Few defended German Americans. On May 21, 1918, the Tacoma Times defended St. Paul Lutheran Church for holding some services in German. They praised the church as patriotic, led by a “pro-American” pastor. Members donated generously to the Red Cross and purchased $10,000 worth of bonds in a recent Liberty Bond campaign. However, the same editorial urged a ban on using German at churches in case other pastors were not so patriotic.

Banning German in Pierce County

Across the country, states and local governments banned German wherever they could. In early June 1918, the Pierce County branch of the National Council of Women Voters started a petition to urge President Wilson to introduce a national ban on the German language press.

Not satisfied with waiting for the president to act, a few days later, the Tacoma Home Guard invited the public to “discuss” their resolution declaring German language newspapers, public meetings, services, and teaching “inimical to the best interests of this country and should be prohibited.”

The group met at the Commercial Club. Only one man, mocked by the newspapers for his accent and “broken” English, dared to speak against the resolution. The Swiss immigrant argued against lumping all German speakers together, declaring, “I speak German, and I am going to continue to speak German.”

But no one listened. Commenters poured scorn on German. “The German language does not need to be preserved for the world,” S. Wade Hampton said. “There is no place for it in the world of today. It stands for everything destructive toward civilization.” Another person claimed to have bought four German papers at a stand along Pacific Avenue before the meeting. The papers, he declared, contained no “real” patriotism and lacked an “American heart.”

According to reports, the unnamed Swiss man got up to leave (shaking his fists in anger), but the Home Guard physically blocked him. As people yelled threats, he was forced to stay and “listen” to the rest of the meeting. His name and address were recorded for possible federal prosecution under the Espionage and Sedition Acts.

The resolution, a recommendation, not a mandate, passed unanimously amidst thunderous applause. German classes did not start the following fall, and churches switched services to English.

Peace But No Healing

While the Allies were victorious in November 1918 in World War I, post-war attitudes towards Germans remained bitter. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in German class enrollment. Most schools, including Tacoma, did not resume German classes until the mid-1920s. But by then, the language had permanently lost its position as the top foreign language.

While German Americans were able to reclaim their heritage with pride eventually, the scars of the war ran deep. My grandfather was born a few years after the war into a German American family in Pennsylvania and attended a German-language church. A US Army medical assistant during World War II, he rarely spoke of his German heritage with his family. But he still loved sauerkraut.