Arguably, one of the Pacific Northwest’s most significant landmarks isn’t a national or historical park. It doesn’t have paid staff or even get steady funding as a heritage site.

But there it sits along Steilacoom Boulevard, where it all started. People drive past the location all the time without knowing anything about how important it was for the settlement of what would eventually become Washington State.

“You don’t expect to see a site of national, historical significance to be in the parking lot of Western State Hospital,” Historic Fort Steilacoom Museum Association President Walter Neary said. “So, Fort Steilacoom is a challenge. It’s hard for people to wrap their brains around it. This whole place is an anomaly.”

The History of Fort Steilacoom

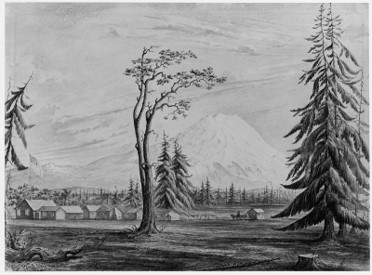

Fort Steilacoom marked the first official U.S. Army presence in Puget Sound, which soldiers founded in August of 1849. It came at a time when the territory was disputed territory between British interests at Fort Nisqually and American settlers who were increasingly flooding into the area, with little regard for the Native Americans who were already here.

The complex history and significance of Fort Steilacoom and the ripple effects to this day can’t be told all at once, so the association is working on several ways to unwrap the tales worth telling. Sure, the fort enabled the flow of white settlers in covered wagons to “go West” under the flag of Manifest Destiny, which led to the United States of America spanning the continent. But the fort also had a part in the changing role of women, and more importantly, fundamentally affected the Native American Tribes for all future generations. All that change started 175 years ago this year, a milestone the association will mark with events, displays and research projects throughout the year.

“This is not a celebration; it is a commemoration,” Neary said.

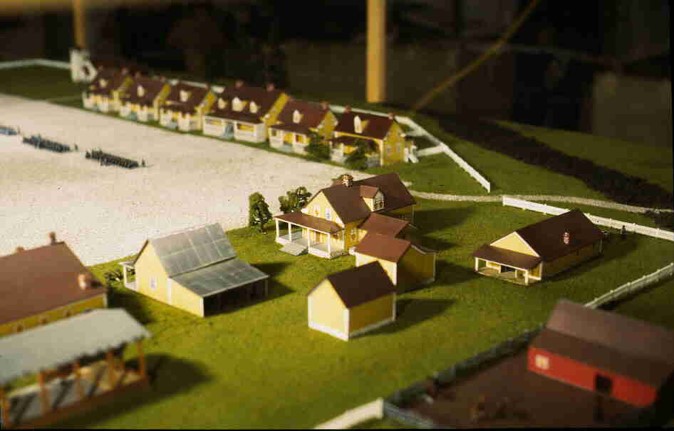

In a nutshell, Fort Steilacoom started modestly on former farmland that Englishman Joseph Heath had settled as a wing of nearby Fort Nisqually. It was expanded throughout the 1850s and served as a transportation and supply depot through the Puget Sound Treaty War of 1855-56. It held Nisqually Chief Leschi as civilians tried him for a murder the soldiers did not think he committed. The fort was active in the “Pig War” of San Juan Island in 1859 and then saw a parade of Southern soldiers and officers resign and process out of the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy as state after state seceded from the Union as the Civil War dawned in 1861. Former friends and bunkmates were now preparing to kill each other. Later, to be famous names like Philip H. Sheridan, George B. McClellan and George Pickett had ties to Fort Steilacoom. Some historians contend that the future general-turned-president Ulysses S. Grant likely visited here while stationed in the area as a captain.

“It had to be incredibly emotional to know that you were going to war with your friends,” Neary said. “It had to be really weird.”

The fort eventually closed in 1868, only to be repurposed as a hospital for people with mental health issues. The former military barracks and buildings housed patients and staff before mostly being replaced by the brick Western State Hospital people see today. Four fort-era buildings remain after local historians fought to save and restore them in the 1980s after being unused and unrepaired for decades.

“The fact that Washington state was willing to let these buildings cave in doesn’t say much about our state’s ability to tell our history,” Neary said.

The Modern-Day Fort Steilacoom

For comparison, Fort Steilacoom’s sibling is Fort Vancouver, which was founded in May of 1849, just three months prior. The two sites are the only Civil War forts in the state. One location is a national park with paid park rangers to give tours and archive the history of the 200-acre site on the border between Washington and Oregon.

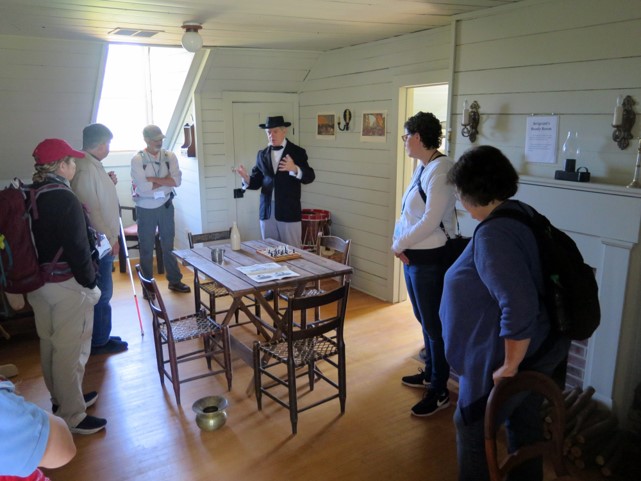

The other is Fort Steilacoom, which relies on donations, volunteers, and grants to tell its stories, and they continue to emerge through research into Native American stories, diaries of settler women, and other minority groups that often get overlooked in the general narrative of history.

“What the volunteers have determined is that we need to tell those stories,” Neary said. “We have moved away from opening our tours with ‘We saved the buildings.’”

The four Fort Steilacoom buildings are open for tours from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. on the first Sunday of each month through the association’s tour site.