Herbert Hoover wrote in a special letter to the Tacoma Times newspaper on October 27, 1917, “I wish I could talk personally to every home in Tacoma about Food Pledge Week, beginning tomorrow. It is such a vital thing and such a simple thing. For it is not a mere phrase that ‘Food Will Win the War.’ Food is the first and most vital of our ammunition.”

As Hoover wrote, food was considered a cornerstone of the American war effort during World War I. The conflict had devastated agriculture in Europe as men marched off to war and fields disappeared under shelling. Submarine warfare disrupted international trade. To top it off, the United States fielded an army. Supplying food for them and the allied nations was now a priority.

President Wilson formed the United States Food Administration to meet the emergency, headed by former mining engineer Herbert Hoover. Hoover had impressed many with his capable handling of relief for civilians in German-occupied Belgium. Over a decade before he became president, Hoover became America’s hero, the head of the U.S. Food Administration. The Times even captioned his photo as “The World’s Real Food King.”

To help the war effort, the Food Administration advocated “food conservation.” Although some laws about consumption and business practices were passed, food conservation was largely a system of voluntary rationing. People were encouraged to save limited commodities, especially wheat, meat, sugar and fats. Through the promotion of “wheatless,” “meatless,” and “porkless” days and meals, people were encouraged to use substitutes such as corn and other grains to reduce consumption of limited foodstuffs.

One of the ways this program advanced was through pledge card campaigns targeted at women who did the majority of cooking and grocery shopping. Through the collaboration of Tacoma’s Commercial Club, Rotary Club, Pierce County Council of Defense, churches and other organizations, Tacomans promoted the last week of October 1917 as “Food Week.” Volunteers canvassed house to house to sign women up. After a week of lessons on the topic, schoolchildren were sent home with three cards for their mothers — a pledge card, a card of directions on saving food, and a window placard declaring their membership in the U.S. Food Administration.

But promoting food conservation did not stop at pledge campaigns. The Tacoma Public Library had poster exhibits, and the Tacoma Parks Department planted potatoes at Point Defiance Park. By October 1917, park employees had harvested 150 bushels and were ready to put them on the market. Schools throughout Tacoma held mass meetings to promote war gardens as residents planted spare lots with vegetables. Volunteers gave cooking demonstrations at PTA meetings, and Gertrude Laycock, a domestic science teacher at Stadium High School, taught evening food conservation classes in room 116. Schoolboys were recruited to work on farms during the summer.

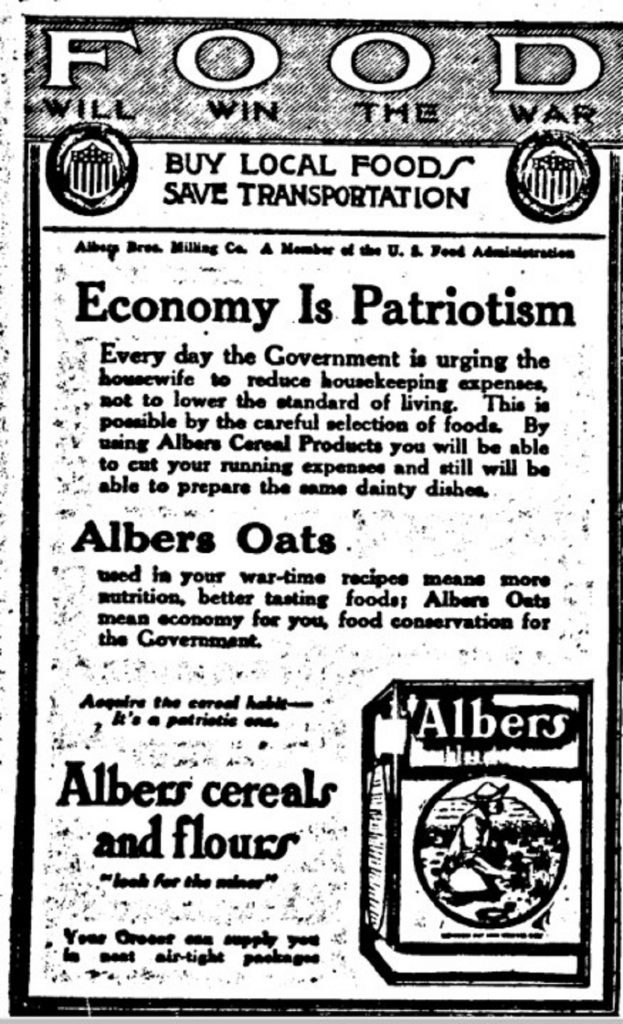

Unsurprisingly, the food industry also supported food conservation. The Tacoma Poultry Association urged residents to raise chickens on table scraps to reduce waste. The McCormick Brothers Department Store hosted several “war bread parties” in their grocery section, offering free buttered slices of whole wheat bread (made with Pyramid flour). An advertisement for one of the events reminded women to bring a pencil to copy the recipe.

Perhaps the most personal window into Tacoma’s wartime food situation is Cynthia Grey’s advice column in the Tacoma Times newspaper. In her column, she typically tackled topics ranging from relationship advice to household cleaning tips. During the war, she received a number of letters on food conservation topics. Letter writers were kept anonymous. Some sent in recipes for canning carrots, making fudge using Karo syrup instead of sugar and baking an eggless, butterless and milkless cake.

Other letter writers used Grey’s column to vent. “A Hooverite,” wrote that one night at work, she had gathered two cups of undissolved sugar from thirty-eight tea and coffee cups. “Corn-Cob” complained that Tacoma bakeries did not sell cornbread and that their “war bread” was unpalatable. A “Foe of Grafters” was outraged to be charged ten cents for two slices of bread at a restaurant. “What thefts are committed in the name of conservation!” the injured party wrote. In her answer, Grey declared that such price-gouging places should be boycotted — ten cents was enough for a whole loaf. And she was right. In January 1918, the Public Market advertised a sixteen-ounce loaf of “war bread” as ten cents. (A pie cost the same, but a dozen “sweet doughnuts” sold for fifteen cents).

Cynthia Grey also published her own food conservation recipes and gave tips on how to save meat. Furthermore, she published instructions for preserving corn and provided recipes for dishes such as corn fritters, corn gems, escalloped corn and corn chowder.

Although World War I’s food conservation efforts ended over a hundred years ago, many of the messages still resound today, though sometimes for different reasons. Ideas about reducing waste, buying local and helping those in need still apply and cooking with new ingredients can yield unexpected culinary treasures.