An odd sport from a bygone era once drew crowds to Puget Sound shores decades ago. It then vanished to become just another weird footnote of local history alongside the mysterious tunnels and Tacoma’s Japantown, only to be “rediscovered” with modern audiences. Welcome to the wonderful world of octopus wrestling, a sport as unusual as it seems quintessentially Washingtonian.

Sit back, relax and read the tale of this cephalopod combat. Octopus wrestling likely checks more than a few “weird boxes” on the checklists of spectator sports. So, keep a scorecard handy.

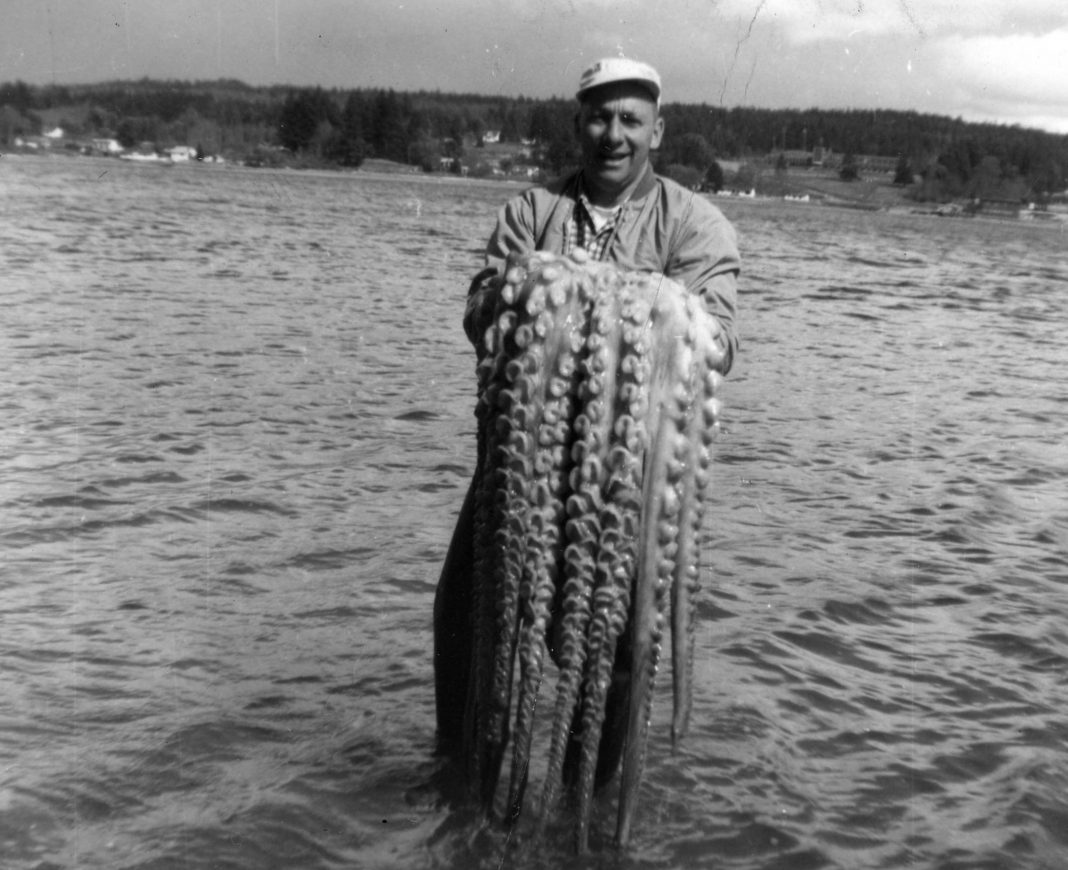

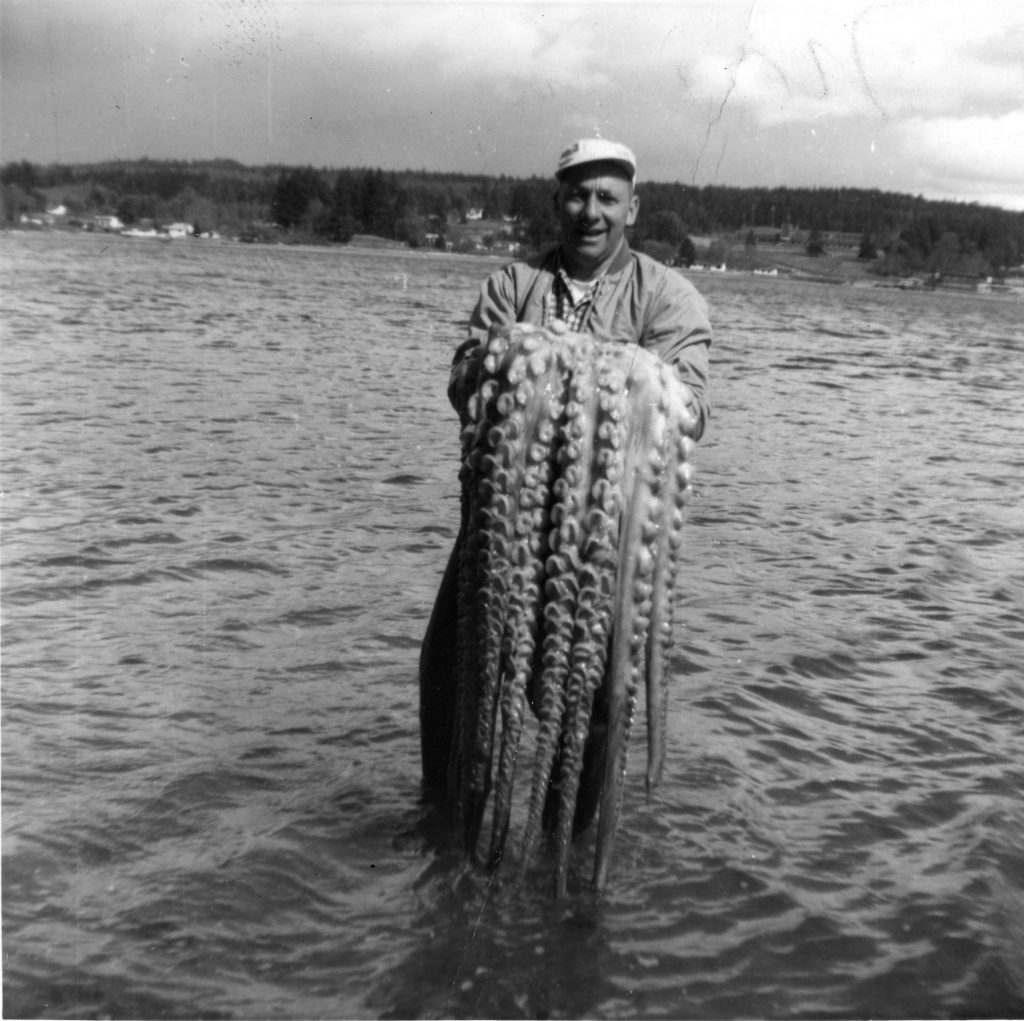

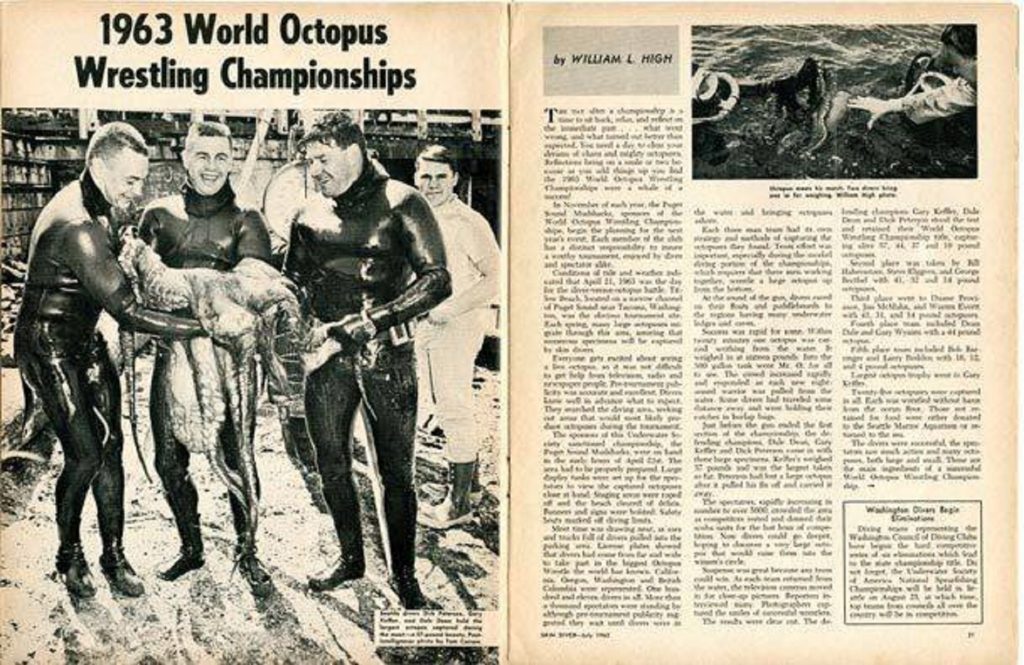

The sport generally involved teams of three divers that would descend into the water at depths up to 50 feet, where they would then find an octopus in its den. One of the divers would then jab its hand down the hole and try to wrestle the octopus to the surface to be weighed before the beast’s tentacles suctioned to a diver’s mask and tore it off, forcing the then sight-deprived to the surface empty-handed. Divers got a point per pound of octopus they brought to the shores if they wore scuba masks and two points if they grappled the eight-legged lords of the water without any modern conveniences. Awards were also given for the largest octopus overall, of course. Most octopuses weighed between 30 and 60 pounds and spanned seven to 12 feet head to tail.

Events started bubbling up in the late 1950s. Divers strategized by either searching for the biggest of the bunch in hopes of landing a heavy beast or go for volume rather than heft. They ran for about a decade and then suddenly vanished when spectators no longer felt comfortable watching people battle with octopuses that simply wanted to be left alone.

“The octopuses had no interest in fighting,” local writer, historian and public speaker Dorothy Wilhem said. “All they wanted to do is go back into their holes.”

Wilhem wrote about the odd sport in her book “True Tales of Puget Sound.”

“It was huge,” she said. “It was as big in those days as wrestling is on television now.”

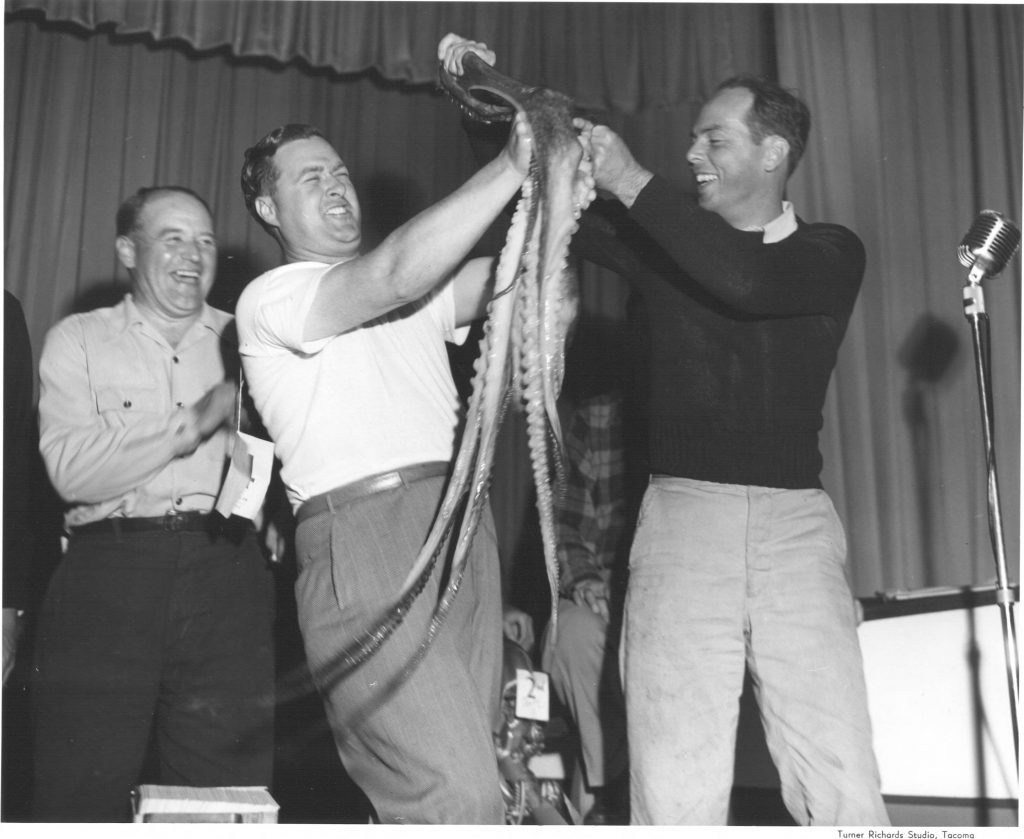

There was probably some overlap in demographic profiles of fans since much of the spectacle of octopus wrestling involved playing up to the cameras and crowds once the beasts of the water breached the surface of the Sound. Octopus don’t have much of a fighting chance once a diver wrestles them free of their rocky home.

Octopus wrestling reached the height of its popularity in the early 1960s. According to most reports, the “World Octopus Wrestling Championships” drew more than 5,000 spectators to the shores of Puget Sound in 1963. The event was reportedly televised. Much like the claims of modern wrestling being staged to wow audiences, crews back then stocked the waters with octopuses before the competition started to safeguard against divers pulling up less-than-impressive monsters from the depths off Titlow Beach as cameras rolled on the spectacle.

Most of the octopuses were then released or given to area aquariums. But some were cooked and eaten.

Local historian and former Tacoma mayor Bill Baarsma never attended an octopus wrestling match during his days of growing up in the City of Destiny. Still, he remembers the splashy headlines surrounding the sport that once promoted his beloved city through tales of massive grapples with eight-legged monsters.

“It was a storyline that got national play,” he said. “I remember reading all about it.”

He doesn’t recall massive crowds or major events at Titlow, as some modern media outlets tell the tales of octopus wrestling from a half-century ago, leading him to believe that promotionally minded event organizers might have puffed up their attendance count to build momentum for future bouts. What he remembers of octopus encounters in Tacoma were much more sedate but ultimately more memorable.

Schools would routinely have field trips to the aquarium, which used to be located along the waterfront. Children would press their noses against the damp glass as teachers would talk about the sea life swimming in the tanks. The animal that always prompted the loudest oohs and aahs was the Pacific Octopus that seemed to dance around the rocks and plants effortlessly.

There was just something magical about reading tales of giant octopuses pulling down ships during high-seas adventures in comic books and pulp magazines, then having national news slash segments on the sport of octopus wrestling, only to see one up close ultimately.

“We were always awestruck as kids,” he said.

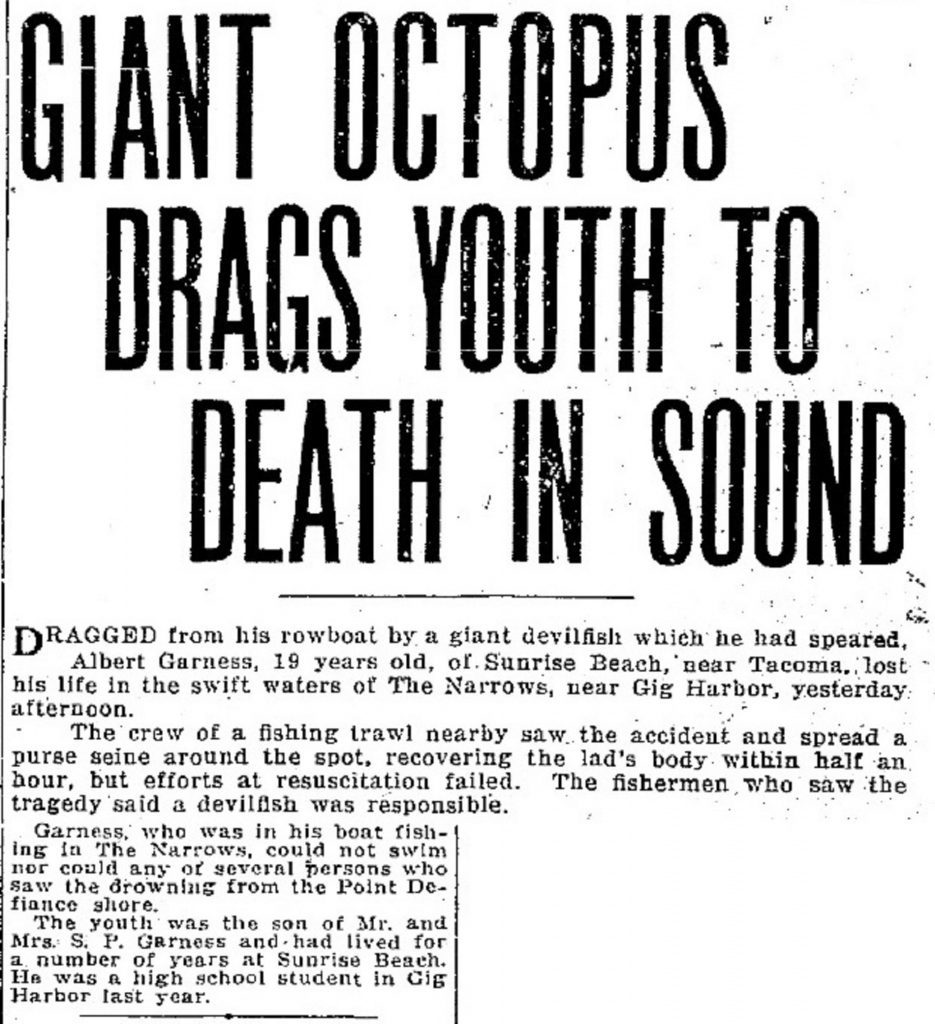

Those encounters, shifts in views about animal cruelty, and Jacques Cousteau’s visit to Puget Sound for part of his 1971 “Octopus, Octopus” documentary changed what people thought about these “devil fish.” Gone were tales of them being mythical monsters out to drown unsuspecting swimmers and drag wholes ships to their watery graves. They were then seen as the solitary, intelligent and graceful ballerinas of the bubbles that they are. The shift in understanding about the creatures, and the general change in mood toward all things conservation, led to the sport of octopus wrestling being outlawed in 1976. The state made it illegal to harass or capture sea life if there is no intention to eat whatever is caught. The law was tightened in recent years by banning all octopus hunting in a half dozen protected areas along Puget Sound, whether for sport or lunch.

Now, as a society, the sport is something we have to grapple with and simply leave the octopus alone.