Danny Marshall, Tribal Leader and Chairman of the Steilacoom Tribal Council devoted his life to sharing and preserving the history of his heritage. Whether through educational outreach or the establishment of the Steilacoom Tribal Cultural Center and Museum, he continues to provide accurate and honest historical information about those that came before us.

A member of the Tribal Council since 1980, Marshall, who is an anthropologist, among a host of specialties, was voted as Leader and Tribal Chairman in 2006.

This was a role that came naturally, having stood alongside the predecessor throughout his life. His mother, Joan (Edwards) Marshall (Ortez), was the Tribal Chair from 1975 until her death in 2006. He is the third generation of Tribal leaders to serve from his family.

His journey as a magnetic storyteller and historian began with traveling to classrooms by her side to share details about the vast Steilacoom Tribal culture. Although not always comfortable in the role of public presentations as a young man, one can see that sentiment quickly faded.

Long before Washington became a state, Marshall’s ancestors thrived in the Tacoma Basin region, not far from what we know today as the city of Tacoma.

The Steilacoom Tribe included five villages spread over the following areas: the Steilacoom, with as many as six sites situated on Chambers Creek (or the Steilacoom River), the Sastuck, with three sites at Clover Creek, the Spanaway positioned at Spanaway Lake, the Tlithlow at Murray Creek, and the Seqwallitchu, with two sites at the Seqwallitchu River.

Traditionally, many tribal people would occupy certain areas temporarily for fishing and hunting, with migration based on what activity was taking place.

“The Steilacoom Tribe was significantly populated to the level that we had five villages that were permanently occupied year-round,” says Marshall. “Some people did not travel out to hunt or fish, mostly elders and very young children, who would stay back in the village.”

The villages typically had one to two longhouses, a large house that usually had several families living together, depending on its size. “Often as many as five families lived within, each with their own independent section of the longhouse,” says Marshall.

Marriages among Tribal people and immigrants were not unusual and even encouraged. They were welcomed as part of the tribe, as well as their offspring. Tribal people looked upon this as another means of strengthening connections, as they continued to reside in their villages and cultivate their identity and traditions.

As Steilacoom Tribal lands continued to draw more and more white settlers, by 1854 it would become the first incorporated town in what was the Washington Territory.

In that same year, the Medicine Creek Treaty was designed to relinquish lands from Tribal people to the U.S. government, in exchange for money, reserved sections of land, or ‘reservations’ created for them away from white populations, and the retention of rights to traditional hunting and fishing in certain areas.

Although the Steilacoom Tribe signed the original treaty, along with a number of Puget Sound Tribes, rather than providing them with a reservation of their own, they were referred to the reservations of the Puyallup, Nisqually, and Squaxin.

Poor land settlements, among other treaty violations, would result in the Puget Sound Indian War between 1855-1856.

The British, who were not pleased to welcome the Americans into a region they had already been active in, were more than happy to arm the Tribes and encourage them to fight against the recent immigrants.

“The Puget Sound Tribes, like the Steilacoom, were leading peaceful lives in their villages during this period,” says Marshall. “There were threats from Eastern Washington Tribes that if we did not participate, we would be enslaved when the Eastern Tribes, supported by militants, came and defeated the Americans.”

Many from the Steilacoom and other Tribes had relocated to a temporary reserve on Fox Island. In August of 1856, this is where Isaac Stevens, governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, would go to reevaluate some of the concerns voiced by Tribal peoples to end the war and unrest during what was called the Fox Island Treaty Council.

Fast forward through a multitude of history, hundreds of treaties, a number of government agencies and departments, and this still didn’t amount to much for the Steilacoom Tribe by way of federal recognition.

“The identification of what would be referred to as a federally recognized tribe is based on seven criteria, one of which is having an Indian reservation,” says Marshall.

One significant change was brought about in the 1930s, however, with the Indian Reorganization Act. Through this development, Tribes were basically assisted in creating their own democratic process within their nations.

According to Marshall, the Steilacoom Tribe was the first Tribe the Bureau of Indian Affairs assisted in constructing their own constitution and bylaws to oversee their tribal government, which is maintained to this day.

Regardless of a reservation, or federal recognition, the Steilacoom Tribe has continued to move forward, maintaining the identity of its people through an active community, political organization, and by combining ancient traditions with the modern world.

In 1989, with the opening of the Steilacoom Tribal Cultural Center and Museum, they became one of only three tribally operated museums in the entire state of Washington. Marshall, along with Tribal members, was instrumental in helping bring about this incredible achievement, creating a permanent location for people to come and learn about their history.

“Historically, there were over 100 Tribes all speaking their own languages in the Puget Sound, and not all of those are around today,” says Marshall. “There are still about 35 tribes, and so many of those don’t have a place to display their history and culture.”

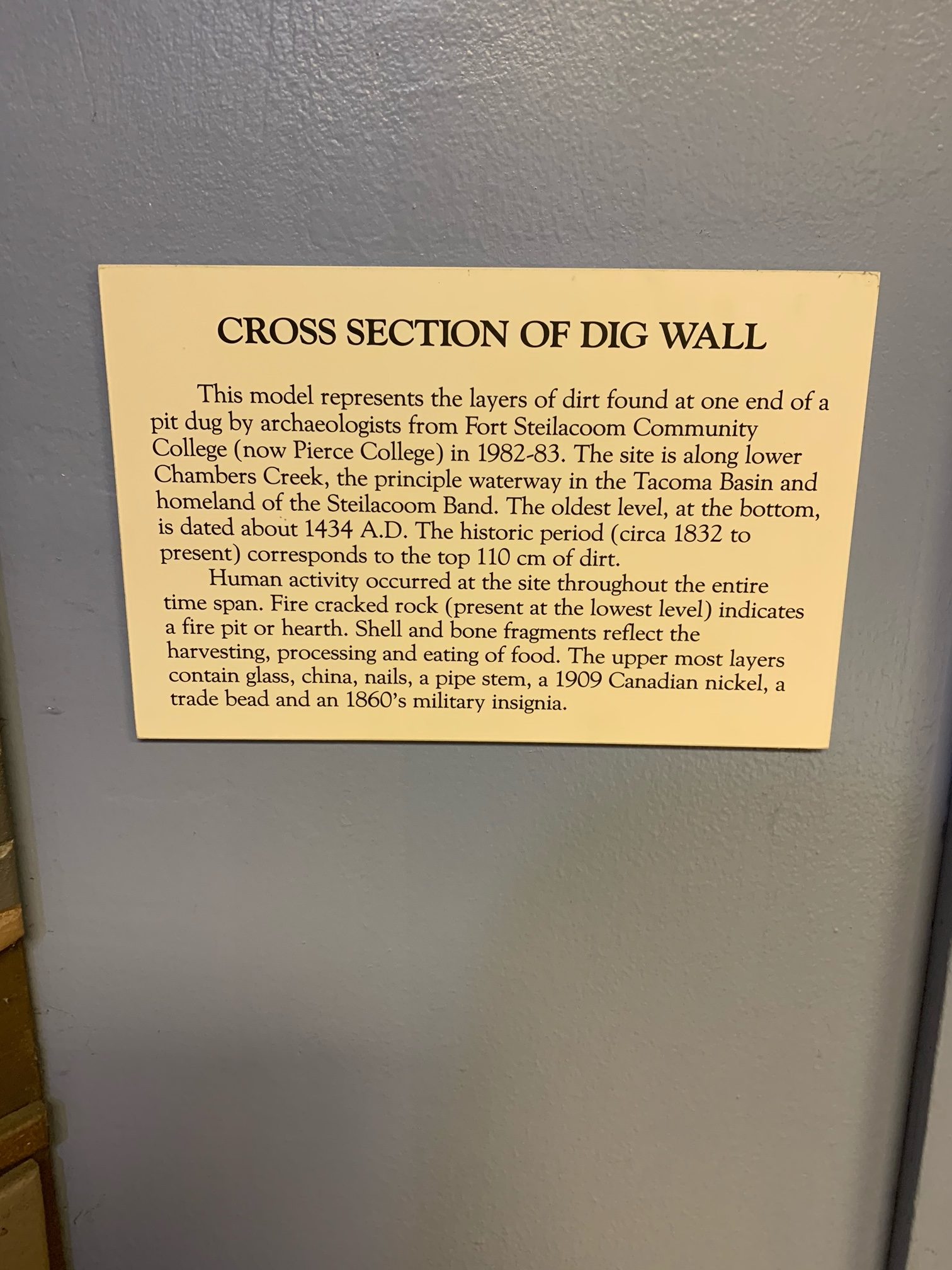

Several excavations were led in the 1980s uncovering artifacts and a glimpse into Tribal life. One such dig occurred between 1982-1983, by Fort Steilacoom College (now Pierce College), near Chambers Creek, one of the areas that were home to the Steilacoom Tribe.

Another took place near there when more artifacts were discovered during a sewer line project in 1988. The Tribe worked closely with Pacific Lutheran University to help with the dig, as well as to document findings.

Guests can view many of the artifacts, historic photographs, and other relics while visiting the museum.

Unfortunately, museums were included within the niche of public event locations that had to close due to COVID-19 guidance. The closures have been very impactful on venues like the Tribal Cultural Center and Museum.

After a brief reopening in October, the museum closed again when restrictions were extended in November. Many non-profit organizations, like the museum, are run solely by volunteers, with several public fundraisers throughout the year, all of which had to be canceled.

“The primary objective for the Steilacoom Tribe has always been about providing accurate historical material to the public,” says Marshall. “The history of the tribe and its involvement in everything that’s taken place here in the Puget Sound and making sure people have access to that is very important.”

Out of hundreds of early tribes in the Washington region, today there are only about 35, several of which have been fighting for federal recognition since the 1800s, one of those is the Steilacoom Tribe.

With Marshall leading, the Tribe continues looking to the future and remains hopeful of reopening the museum soon, as the state moves into Phase 2 of its guidance plan. The Museum is located at 1515 Lafayette Street in Steilacoom.

Check here for future updates on museum reopening and hours.

You can support the Steilacoom Tribal Cultural Center and Museum by joining the Steilacoom Tribal Museum Association here.