The Puget Sound, and the world for that matter, isn’t a stranger to outbreaks of ailments, epidemics or worried brows every time someone sneezes or coughs. Modern Tacomans might find some comfort in the fact that epidemics have come and gone throughout its history. One of the first was an outbreak of smallpox in 1881, a virus that could have doomed the new city had it not been for one man. And then it was all but eradicated around the world by yet another Tacoman a century later.

Let’s start at the beginning and go from there.

Herbert Hunt’s “Tacoma: Its History and Its Builders, a Half Century of Activity,” published in 1916, recounts how a Civil War veteran worked tirelessly to keep smallpox from claiming countless lives along Puget Sound.

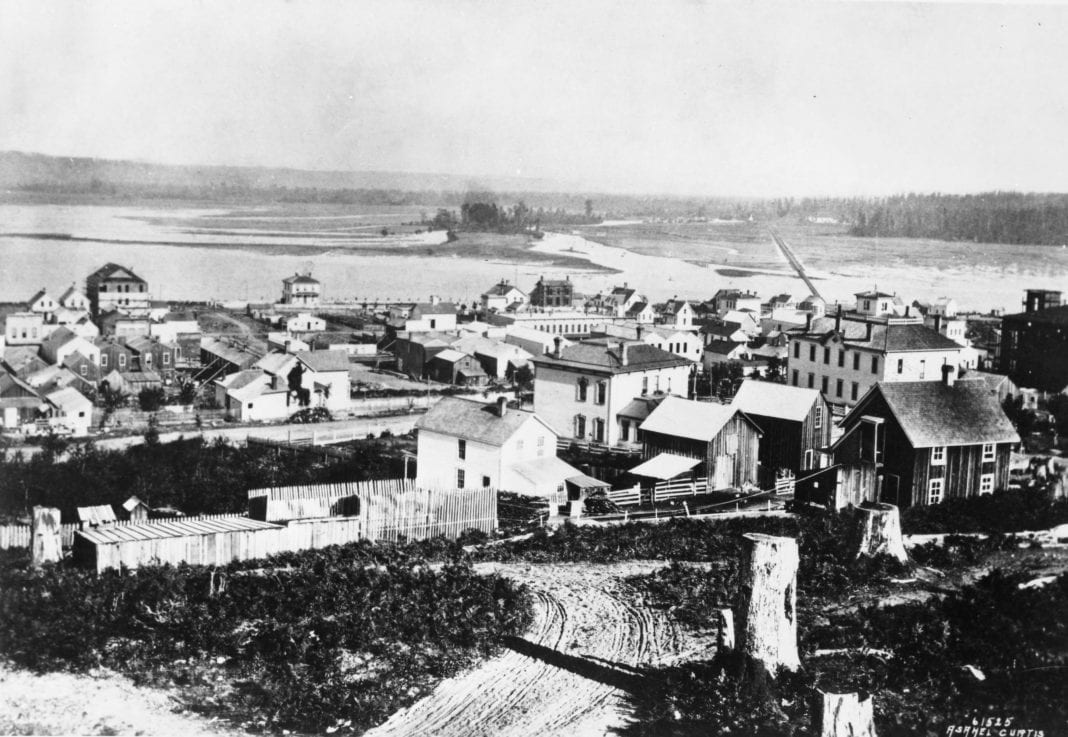

Smallpox came knocking on Tacoma’s doors in the fall of 1881 and quickly sent many Tacomans to their beds with high fevers and skin rashes. Keep in mind that there were still two Tacomas at the time. New Tacoma had just stolen the title of county seat from Steilacoom the previous year and the Civil War General and Medal of Honor recipient John W. Sprague wouldn’t be elected to serve as the first mayor of consolidated Tacomas for another two years.

But the virus didn’t honor municipal borders. Smallpox is highly contagious and has a high fatality rate, making it one of the most feared ailments of the era. Even if people survived the fever, they were often scarred for life by the rash or blinded by the ailment.

The first cases were traced back to a man who lived on Pacific Avenue. His father in law would die, while he and his four children edged toward death. As fate would have it, the man had served as a waiter at the Halstead House, and had infected several of his patrons before he fell too ill to report for work. His last shift was spent serving a celebratory dinner that followed the installation of lodge officers of the nearby Knights of Pythias. The hotel’s proprietor immediately sought to allay fears that his establishment was the source of the first spark of cases by advertising in the local papers denouncing anyone who would say otherwise.

But the numbers told a different story. Tacoma had a problem.

“The contagion was widely distributed that autumn, scarcely a city on the coast escaping, but none had a worse experience than Tacoma. Two adults and a child had died before the disease was diagnosed as smallpox,” Hunt wrote in his must-have history of the area. The initial delay in governmental action came after some doctors – including Henry Clay Bostwick, who was the area’s first physician and builder of the downtown building that still bears his name – wrote openly in the local newspaper that the ailment was not smallpox but cases of the less-severe chicken pox.

It should be noted that, while Bostwick was a physician who partnered with Dr. Francis Bond Head Wing in a medical practice, he was also a founder of the Bank of New Tacoma. He might have let his financial stake in the new city’s commerce cloud his medical judgment by downplaying the ailment in an open letter in the “Tacoma Daily Ledger” that there was “no cause for alarm,” when there were clear cases of an outbreak.

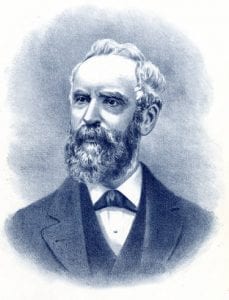

Wing quickly ended his business ties with Bostwick and was then appointed the city’s first health officer after he feared the worst. His fears proved correct and he fought the false sense of public safety promoted by his former colleague, who held fast on the chickenpox diagnosis. The new city had about 1,000 residents, and the fever hit upward of 150 in a matter of weeks. About 50 would ultimately die, according to some accounts. But it could have been worse had Wing not convinced Mayor David Lister to seek an outside opinion from Seattle’s health officer that concurred with Wing’s diagnosis and then championed quick and drastic action.

“The town was shut off completely from intercourse with its neighbors,” Hunt wrote. “The trains ran through with windows closed, and at the wharf, they entered a stockade, in which the transfer of passengers to and from the boats was made. The townspeople, outside of those who lived in the corral on the wharf, were not permitted there. They could not take trains or boats out of the city. Puyallup and Steilacoom established a shotgun quarantine to prevent persons from the stricken town from reaching these two places. Barricades were built across the roads, and behind the barricades were armed men. Weeks passed with no money in circulation. The grocery stores in many cases set their deliveries on stumps near the stricken homes. Several of the stores closed entirely. Churches and schools were closed and all assemblages forbidden. Funeral after funeral was held in the night.”

An outdated steamer, the Alida, was even renovated on the fly to serve as a floating hospital after anchoring in Commencement Bay. Rowboats delivered patients every day. Tacomans sought cures and precautions wherever they could. William P. Bonney, who ran a drugstore on Pacific Avenue at the time, charged patients a few cents to sit in a room filled with burning sulfur in hopes that the fumes would ward off the virus. He also sold tins of carbolic crystals on the idea that just having the minerals in a person’s pocket would guard the carrier from “the pox.”

Wing did not rest after the city was locked down. He visited patients around the clock not only to save as many people as he could, but to keep the scourge from spreading to neighboring houses, nearby streets or workplaces of anyone even suspected of being contagious. He feared a long and deep epidemic could doom the city before it was even allowed to boom. So he visited the sick when no one else would and tended to their needs when their neighbors abandoned them to their fate.

The smallpox plague was contained and city life slowly returned to normal by the middle of December. But it had taken its toll, not just on the city but Wing himself. Wing’s official tally was 80 cases that left 14 dead, but modern researchers believe the butcher’s bill was likely higher. History would show that it would take at least one more than Wing’s final report would list – Wing himself. He had worked himself beyond his limit. His friends worried about his health. They urged him to take a vacation once the epidemic cases slowed to a trickle. But it was too late.

Wing made plans for a vacation and made his rounds to say goodbye before he returned to his office to shudder his doors for some well-earned time off the night of January 14, 1882. He planned to leave the following morning for a two-week vacation to San Francisco. But it was not to be.

“He was not again seen alive,” Hunt wrote. “About two days later, an investigation revealed his dead body. Death had come to him while he slept, and it was the death of a true martyr.”

He had been a widower and lived alone, so no one suspected anything odd when they didn’t see him. They all thought he had left for his trip. He was found dead in his bed on Sunday. He was only 43. The Canadian born doctor and survivor of the Battle of Shiloh had given his life serving the residents of his adopted city. While he is buried in Tacoma Cemetery, nothing on his headstone or online obituary note the fact that he saved the city from smallpox.

Tacoma’s ties to smallpox would not end there, however.

A Pacific Lutheran University graduate by the name of Dr. William Foege would go on to develop what is known as “ring containment” of smallpox outbreaks that would prove so successful that smallpox would be eradicated from the planet in the late 1970s. He would be honored for being such a public health hero in 2012, when President Barack Obama would award him the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his lifetime of achievements in international public health, particularly regarding smallpox containment and eradication.