Maybe it’s because Tacoma is a true melting pot that creates a stew of bold, rich characters and salty tales that writers crave to record on paper. Maybe it’s because the city was born from lumber, pulp and paper making on which to write. Or many it’s because people still flood into the area to write their own next chapters. But whatever the reasons, the Puget Sound has links to literature that continue to shape both the written word and the city itself.

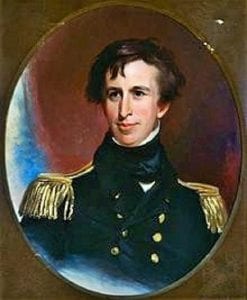

Herman Melville

Herman Melville’s sea-faring novel “Moby Dick,” for example, is a must-read for many American high schoolers to this day. It’s a whale of a tale about the insanely obsessive whaling Captain Ahab, who seeks the white whale at all costs. Anyone who has read the book or seen movie variations might not notice that it is based on a character well known to Puget Sound. He was Lt. Charles Wilkes.

Wilkes enforced harsh discipline, including excessive use of the cat-o’-nine-tails on the bare backs of his disobedient men. He was so abusive that he faced a court martial when he returned to Washington, D.C. The military hearings were front-page news on the East Coast. Interestingly, Melville not only read those articles and incorporated details of Wilkes’ “Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition” into his masterpiece, he also drew from personal accounts since Melville’s cousin, Henry Gansevoort, had been an officer during part of the voyage. Melville’s work marked a shift in nautical fiction away from romanticized settings to the more brutally realistic portrayal of a life at sea.

George Francis Train

Another local with ties to literature was George Francis Train. He financed the Northern Pacific Railroad’s route to the West Coast that ended in Tacoma. He promoted the “City of Destiny” as a way to maximize the return on his investment in the railroad and regaled crowds around the nation with stories of untapped wealth just waiting to be made in the booming town.

In 1871, Train wanted to set a speed record for going around the world, so he left New York on a Union Pacific train and arrived in San Francisco seven days later. He took the Great Republic clipper ship to Yokohama, then moved on to Singapore, where he learned of the revolution in France. He was imprisoned in Lyons for his revolutionary activity, but released after 13 days, when he then chartered a train to the English Channel and sailed from Liverpool to New York. When he arrived, he claimed to have gone round the world in 80 days. No one checked his math or asked about the time in jail.

His trips around the world, however, were covered by many newspapers and inspired Jules Verne’s 1873 novel “Around the World in Eighty Days.” The novel’s protagonist, Phileas Fogg, is believed to have been modeled on Train, who would break his old record in 1890, with a trip of 67 days that began and ended on Tacoma’s Broadway.

Rudyard Kipling

It was also around this time that the yet-to-be-famous British author Rudyard Kipling visited Tacoma on his way to India to find inspiration. The 23-year-old traveler witnessed a town on the rise with brick buildings rapidly replaced wooden shacks. His description of Tacoma being “smitten by a boom” is vivid, condescending and comical: “The rude boarded pavements of the main streets rumbled under the heels of hundreds of furious men all actively engaged in hunting drinks and eligible corner-lots. They sought the drinks first.”

Kipling fit in with the rough and tumble town, particularly since no one had any idea who he was. It was only later that he would be an icon of literature, with the publication of “Gunga Din” in 1890, “The Light That Failed” in 1891, and “The Jungle Book” in 1894, all books he was working on during his travels through Tacoma.

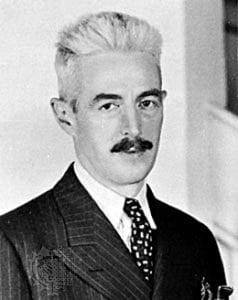

Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett is considered a father of the hard-boiled detective genre, also known as crime noir. His work centers on the tragically flawed, anti-hero of Sam Spade. That character is firmly planted in Tacoma since Hammett came to city in the fall of 1920 to get treatment alongside other “lungers” and shell-shocked vets at the Cushman Hospital. He had caught tuberculosis during Great War.

Hammett would stay long enough to read about shootings, ax murders, corruption and vice. He would watch the city wobble under the financial collapse of the Scandinavian American Bank, where one in eight residents had accounts. Hammett left after a few months to begin his writing career, always keeping Tacoma in mind. He gave the city a bit of a literary shout out in the “Flitcraft Parable,” a short aside in the “Maltese Falcon.” The story has a chap named Flitcraft having a near-death experience only to abandon his life and family in Tacoma. With children to care for, his wife hires a detective to find him. Flitcraft turns up in Spokane. He is living a life strikingly similar to the one he fled in Tacoma, creating a parable about chance and destiny.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Shortly after Hammett left, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – the author behind the world’s most logical, albeit also fictional, detective – also paid a visit to Tacoma. Doyle had just published “The Case for Spirit Photography,” which included a collection of images reportedly showing ghosts in the form of blurs and mists or partially distinguishable faces. One of them was of the author and his son, four years after his death. His book’s publication prompted a promotional tour that brought the crafter of Sherlock Holmes to Tacoma in June 1923. His talk was covered by the Tacoma Daily Ledger, which described the ghostly goo as “a plastic substance, not yet fully understood, which comes from the body of the medium.”

Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert was just three-years-old when Doyle visited his city. The Tacoma-raised author of the sci-fi classic “Dune” witnessed a much different city than the one boasted about by earlier travel writers and promoters. He saw environmental degradation, industrial pollution and waste, all themes that set him apart from other science fiction writers of the time. They largely created a tales where technology answered all of life’s concerns. Herbert crafted dystopian worlds where technology created life’s ills. He wrote about what he knew, since he saw it pay out from his bedroom window as a child of Tacoma.

His role as a warning light against unchecked industrialization led to Metro Parks of Tacoma naming its latest park after him and his works, all part of a cleanup effort of a contaminated waterfront site along the working waterfront that raised such concern for Herbert.

It should be noted that the effort to honor Herbert was championed by Metro Parks Commissioner Erik Hanberg, an author turned politician who has published several novels including “The Lattice Trilogy.”