Modern sailors, soldiers and airmen can thank a Tacoman for the information about their branch, base or theater of operations they read in the Stars and Stripes newspaper. For it was a Tacoman who founded the paper during the early days of World War II and left his mark on journalism along the way.

Ensley Llewellyn grew up in Tacoma, while his father operated a marketing and advertising firm in University Place. Llewellyn graduated from Lincoln High School and then attended the College of Puget Sound, as University of Puget Sound was called back then, and Washington and Lee University in Virginia. He then enlisted in the Washington National Guard and found himself mobilized for federal service as America prepared for war.

It was most certainly at this time that he first brushed shoulders with Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was commanding 1st Battalion, 15th Regiment at Fort Lewis at the time.

Eisenhower had received his first general’s star just two months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor and his planning and administrative skills called him to the European Theater of Operations under Gen. George C. Marshall to handle the logistics of the waves of fighting forces already en route to England.

Those soldiers and sailors were going to need information from home as well as news as they headed into harm’s way. Eisenhower handpicked Maj. Llewellyn for the task.

“Llewellyn was certainly the right guy to do it,” said Richard G. Patterson, vice president of the executive committee of The Arsenal Museum that operates on Camp Murray thanks to the Washington National Guard State Historical Society.

Llewellyn was resourceful, had a deep background in printing and was a skilled planner. Llewellyn even spent his own money to cover expenses not funded by his military budget. The first issue, which was published in London as an eight-page weekly on April 18, 1942, and ran an address from Marshall about the purpose of the newspaper.

“A soldier’s newspaper, in these grave times, is more than a morale venture,” he wrote. “It is a symbol of the things we are fighting to preserve and spread in this threatened world. It represents the free thought and free expression of a free people.”

The newspaper sought to battle the Nazi propaganda that was making its way into Allied lines as well as inform and entertain soldiers. The Stars and Stripes proved an immediate hit with the troops because its pages contained extensive coverage of sports. It ramped up quickly to become a daily newspaper by the fall. It was even turning a profit, which went to Army welfare and recreation efforts.

Llewellyn was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the fall of 1943 and took on the duties of publishing pamphlets as well as working out the logistics and practices of radio broadcasting from the front lines without affecting military secrecy.

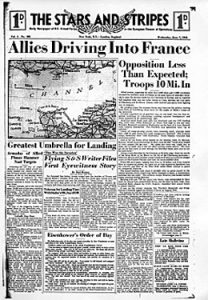

Not one to lead from his desk, Llewellyn jumped into action when he learned about the Allied landing of Operation Overlord on June 6, 1944. He found himself with a small staff of press operators and journalists in Normandy, France, alongside the famed 101st Airborne Division. Newspapers found themselves in the hands of soldiers by morning, recapping news from home as well as news from the previous day’s events.

Popularity and circulation boomed because the Stars and Stripes was the “for soldiers, by soldiers” newspaper. Soldiers, for example, donated money through the newspaper to aid war orphans and were also able to order gifts from Paris they could then send home through the newspaper’s Shopping Service section.

By war’s end in 1945, the Stars and Stripes published editions in 16 theaters of operations with a daily circulation of about two million. Llewellyn returned to Fort Lewis to end his service in the regular army with a Purple Heart and Legion of Merit for his leadership of the newspaper.

He then worked at the Llewellyn Advertising Agency. That stint didn’t last long. Washington Gov. Monrad Wallgren appointed him in 1947 to serve as Adjutant General, commander of the Washington National Guard with the rank of brigadier general.

He then retired after 30 years of military service in 1951. Llewellyn would go on to serve stints with the regional committee of the YMCA, the Washington Department of Civil Defense and an advertising organizer of some 500 political campaigns. He died at the age of 83 on July 19, 1989. His obituary appeared in the pages of the Stars and Stripes as well as the New York Times and his funeral services were scheduled Tuesday at University Place Presbyterian Church.

Militaries have had newspapers during wars for centuries. The Union Army even used the name Stars and Stripes for its soldier-focused newspaper during the Civil War. The name was also used during World War I only to cease operation each time, once the guns fell silent. Llewellyn’s efforts, however, proved so successful that his newspaper survived when World War II ended. It has served soldiers in war and peacetime ever since and continues to publish around the world to this day.

Yet his story is one that is largely overlooked. There is, however, the National Stars and Stripes Museum and Library that tells the ever-changing story of the newspaper Llewellyn brought into the modern age more than a half-century ago.