The two-story building at 309 South 9th Street called Hosmer House seems out of place in downtown Tacoma because it is wood framed in a sea of brick and mortar on a main street, and because it is painted bright yellow. Its uniqueness goes beyond those cosmetic features. It not only served as the home of the founding father of Tacoma, but survived the construction of skyscrapers around it.

“It is arguably one of the—if not the—most historically significant houses we have,” said Historic Tacoma member Marshall McClintock, who wrote the historical designation nomination back in 2016 that landed the house on the city’s Register of Historic Places. The house had been through cycles of use and disrepair and renovations as the decades passed. “There had been several times when it was close to being torn down.”

But the Hosmer House apparently had a fighting spirit, much like the city itself and the house’s first resident, Theodore Hosmer. The 143-year-old building is the oldest residence in downtown, and served as Hosmer’s home while he played a key role in the development of the city before going on to serve as its first mayor. Hosmer would see the buildings of the fledgling Western outpost mushroom around the landscape both from his bedroom window as well as from his real estate office across the street.

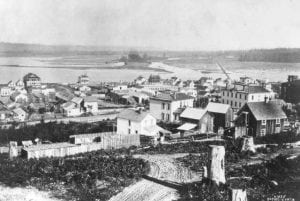

See, Hosmer was the special agent of the Tacoma Land Co., a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The railroad had selected Tacoma as the terminus of its transcontinental railroads in 1873 and tracks were already being laid toward Tacoma’s deep seaport. The company needed someone to map out the railroad’s land holdings, which would then be sold to the people and businesses that were most certainly going to come with the trains. Hosmer and his wife, Louise, were on the scene from the start, living first in a tent on a wooded hillside of what is now the City of Destiny, while the Northern Pacific Railroad built their home.

Hosmer designed this Italianate-style house himself, but left the construction to P.D. Forbes. The Hosmers moved in shortly after it was completed in 1875 at its original location at what is now 750 Saint Helens Avenue. It sat at the center of the city, with a wooden City Hall across the street and right next to the offices of the Tacoma Land Co. and the railroad headquarters. Hosmer’s commute to work was measured in feet. Life in a mansion that was specifically built just for him came with his position, which just might have also come from family ties as much as his ability. He was, after all, the brother in law of Northern Pacific board member Charles Wright.

Regardless of how he landed the job, Hosmer’s mission was daunting. He had to create a city from a wooded hillside in a way that would ensure success to the boomtown, while maximizing profits for the railroad. He was good at what he did, apparently. Hosmer received a promotion to Tacoma Land Co.’s general manager in 1877 in a town without an official city government. He was, by all accounts, the most powerful man around. That power of influence became official when he left the railroad and formed the New Tacoma’s first official government. He added the title of mayor of New Tacoma to his resume in 1882. If you aren’t familiar with New Tacoma: the railroad selected what is now downtown Tacoma as the terminus. The town was called New Tacoma, which was about a mile away from Tacoma City, which became what is now Old Tacoma. Both Tacoma City and New Tacoma had separate city councils before the cities merged later on.

The Hosmers would leave Tacoma after less than a year of his term in office, however, when Louise fell ill and forced the family to move to Philadelphia. Old Tacoma and New Tacoma would merge two years later, while Hosmer was tending to his wife, who died in 1885. Hosmer then came back to the city he formed and again worked for the Tacoma Land Co. He also became the president of Tacoma Light & Water Co., president of the Wilkeson Coal & Coke Co., and director of the Pacific National Bank. In his spare time, he also founded the University-Union Club, the Tacoma Yacht Club, and Tacoma Theater Co. He also served as a trustee of Annie Wright School and was a charter member of the Washington State Historical Society. He died in Tacoma of a stroke in 1900.

As for his house, it had become an 18-room boarding house in 1887. It was then moved from Saint Helens around the corner to 9th Street in 1904 to free up the high-profile site for commercial development. The founder of the Rhodes department stores renamed the building when he bought it a decade later. It became The Exley, a name it bares to this day. It was named after Henry Rhodes’ father ancestral hometown in England.

Brick buildings grew up around it as Tacoma grew. Rhodes almost had it torn down to make way for his Medical Arts Building in the 1930s. Instead, his investors pointed out that a nearby site would be better for his 17-story building since the alternate site would allow the building to have two entrances, one of Market and one on St. Helens. That fact saved the Hosmer House the first time. Of course, the Rhodes Medical Arts Tower is now known as Tacoma Municipal Building.

The Hosmer House continued as an apartment, but was showing its age after being neglected for years. It was again slated for demolition to make way for a parking lot in 1975. It was condemned and red tagged. The parking lot plans died. By 1980, a new owner took over the property and renovated the building and gave it yet another lease on life as a 12-room apartment for clients of the nonprofit Pioneer Human Services, and agency that provides people with criminal records, substance or mental health challenges with second chances – a decidedly Tacoma trait.

“This building is central to the story of Tacoma,” said McClintock.