Submitted by University of Puget Sound

Moses Lee was thinking. Here he was, program director for research and science at the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust, a man with an unbridled passion for science and a philanthropic pot of money needing a good home.

His task? To find a way to advance science research at four-year colleges in the Pacific Northwest region that the peregrinating Canadian native had come to call his second home.

So what to do? He picks up the phone and makes five calls to five university researchers. Some of them live hundreds of miles apart, all are at different stages in their careers, and most have never met. They don’t even all work in the same field.

There were the chemists: Carlisle Chambers at George Fox University; Andrea Munro at Pacific Lutheran University; and Mark Bussell and David Patrick at Western Washington University. Then there was the lone physicist: Amy Spivey at University of Puget Sound.

“Out of the blue, Moses called each of us,” says Spivey. “He said, ‘I’m trying to bring together a group of scientists who do research with undergraduate students to collaborate. I would love for you to meet and see what ideas you can come up with.’” The prospect of a $240,000, three-year grant and some exciting work for their students no doubt sent a few test tubes crashing to the ground.

You could say that Lee is a puzzle master, pulling together a scattering of jigsaw puzzle pieces to see what the final picture looks like. Or you could say that he is on to something.

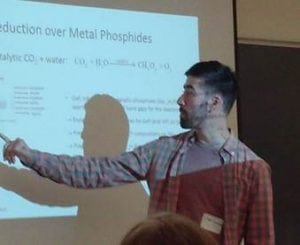

The humble company of five researchers, calling themselves the Murdock Collaborative Research Alliance, decided to tackle one of the toughest issues plaguing the global solar energy industry—the high cost and limited efficiency of solar energy. Their work, currently underway with the help of 10 students, is at the cutting edge of science, involving luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs)—promising, but finicky, devices that collect sunlight over a large area, then focus it and convert shorter wavelengths into longer wavelengths. This low frequency radiation can then be converted into electricity in photovoltaic solar cells.

In principle the LSCs could work under cloudy skies and with no need to track the sun, making them more cost efficient than solar dish concentrators in cloudy environments. Researchers have struggled for more than 35 years to find the right luminescent materials and create a model that could be applied at an industry scale.

Golly. But hold on. This solar work, intriguing as it is, is really just the “experiment within the experiment.” While the researchers are scrutinizing nanoparticles for use in future LSCs, Lee and the Murdock Trust are keeping tabs on them. The trust’s Science Research Program wants to learn how well small colleges, backed by the lab resources of a public university, and bound by their administrators’ shared commitment, might work together—across distances and across disciplines.

Toward what end? The professors and students, now one year into the project, offer some clues.

“Before we started I was pretty convinced I would be here a couple of months and find something huge,” quips Liam Carmody ’18, a lanky chemistry major at Western Washington University. “Now I know that is pretty unlikely, but just knowing we could make one discovery in the right direction is a huge motivation.” Giving a little bow after presenting the Bussell Lab’s work to his fellow researchers at a gathering at University of Puget Sound this summer, Carmody admitted that the results so far are “inconclusive.” Nonetheless, he says, he dreams of seeing the work scaled up to industry size.

Says Carlisle Chambers, chemistry professor at George Fox:

“The experience is terrific. It really energized my work. And it’s great for the students to see how science works in terms of the networking and collaborative nature of it. They are understanding how science gets done.”

Andrea Munro, associate professor of chemistry at Pacific Lutheran, feels likewise. “It has sharpened my focus and encouraged me to seek more institutional support for grant proposals. It’s got my people excited about the prospect of doing more research,” she says.

The Murdock collaboration, an unorthodox template in the science funding world, is a rare opportunity, adds Amy Spivey, physics professor at University of Puget Sound. “Normally, it’s difficult for people at small colleges to find collaborators, because the departments are smaller and the faculty spend much of their time teaching. But with this collaboration we may engage 15 to 20 students over three years, and who knows what science they will go on to do?” she says.

Of course the research model has its issues. Part of an experiment may depend on another researcher’s results, so you just have to wait. Exchanging progress reports often means long conversations over Skype—sometimes at odd hours. Glass vials of organic matter from Chambers’ lab have to be bubble-wrapped and mailed to Munro, who incorporates inorganic matter, creating a bright orange nanocrystal. Her creation is driven over to Spivey to analyze for its optical properties, and any promising samples are finally delivered to Patrick’s lab for the critical trial in one of Western Washington’s luminescent solar concentrators.

“There’s no one working just down the hall,” sums up Chambers ruefully. The big “crunch” for the team is looming. They plan to apply for a National Science Foundation grant this fall, in the hope of funding further research, beyond the Murdock term.

Overall, the “experiment” appears to be going well. Both of them, that is. And if the human one works (Lee defines “success” as showing the multi-campus research model can be “successful and sustainable”), the Murdock Trust may initiate more grants using this protocol. Such an expansion could inspire other funders to try something similar. And who knows what science these small colleges and their students could go on to do?

To be sure, it wouldn’t be the first time the Pacific Northwest has sparked a nascent cultural revolution (think music, coffee, technology) that ultimately could touch lives everywhere.