July 4, 1900, started out as just another day in Tacoma, albeit one that promised celebration of Independence Day. The day would close with heartache and tears in what would go down in history as the country’s worst streetcar disaster. And its story is just now being fully told in a new book “The Fateful Fourth: The Story of America’s Worst Trolley Disaster” by local historian and author Russell H. Holter.

The Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation staffer won the Tacoma Historical Society’s 2016 Murray Morgan Award for his work on local history and spent decades piecing the incident together to provide a candid, detailed and sometimes grizzly treatise in an effort to separate fact from fiction. Ultimately, the incident left 44 people dead.

“The more research I did on it the more questions I had,” he said.

Like most dives into historical matters, Holter found piles of news articles about the incident and its aftermath, often noting that many of the articles were either brief, summarized the same details, conflicted each other or were more fiction than fact. That’s a common frustration modern historians have with newspaper articles from the age of “yellow journalism,” when fact meant less than selling newspapers.

“You have to read those with a lot of grains of salt,” he said, especially in accounts that bubbled up in the media circus that came to town in the months after the disaster from every angle.

The basics of the story are pretty straight forward and much like the sinking of the Titanic, involved a bit of hubris, lack of safety procedures and ignorance of basic laws of physics.

Tacoma Railway and Power Co. streetcar No. 55 had malfunctioned, so its passengers waited a few minutes and hopped onto the next car. At around 8:00 a.m. on that dewy summer morning, streetcar No. 116 pulled away from a stop in South Tacoma to downtown after switching from the Point Defiance Line to the South Tacoma Line to accommodate the added ridership that was expected. The Independence Day parade was expected to draw 50,000 people, after all.

The streetcar was built to hold 55 people, but three times that number managed to cram themselves aboard (some standing on the running boards or hanging from the support railings) by the time it reached the station at 34th Street to get one last passenger. A boy hopped on right as the streetcar crested the hill on Delin Street.

Physics took over from there.

The streetcar gained speed. The brakeman, F. L. Boehm, applied the brakes but couldn’t slow the car. Then he put the electric motor in reverse. That didn’t work either. Passengers began to notice. Some were thrilled since many had never traveled so fast in their lives. Others began to worry. Some jumped off as the car accelerated, other people tried to jump but couldn’t wiggle free from the mass of humanity. The miscalculation turned into a disaster at the bottom of Delin Street at South 26th Street. The car, which normally traveled at about 10 miles per hour, was dashing at 50 miles per hour and well out of control.

The car jumped the tracks at an almost L-shaped curve that would have taken the streetcar onto a trestle at C Street, now Commerce Street. The trestle spanned the 100-foot deep “Gallagher’s Gulch” that is now South Tacoma Way. The streetcar was traveling so fast that it jumped over a guardrail that had been installed as a safety feature.

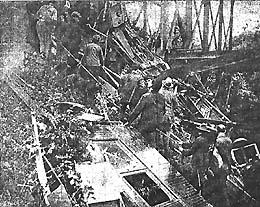

Passengers flew into the air as the steel beams from the streetcar created a swirl of twisted metal and sprays of shattered glass.

“It turned into a giant Veg-o-Matic and chewed people up,” Holter said, noting that with an average weight of 100 pounds per passenger, the streetcar carried 14,000 pounds of victims. “That’s seven tons of flesh” that was suddenly thrown into the air to mix with shards of broken window and spinning bits of steel.

The streetcar landed upside down after tumbling down the hill. Bodies of the dead, dying and injured landed yards away during its plunge. Bloodied and broken bodies left a landing strip of carnage along the hillside. The first emergency responders to arrive were Tacoma Police officers who were getting dressed for the Independence Day parade later that morning. They arrived in their parade regalia and immediately set out to rescue survivors. Ambulances, firefighters and everyday civilians swarmed the scene to provide whatever aid they could.

Their rescue efforts quickly turned into a mission of body recovery. The final tally on the butcher’s bill was that of the 141 passengers who boarded the streetcar 44 dead, 37 didn’t even survive the day. More than 70 suffered broken bones, cuts, and sprains.

A coroner’s inquest concluded 10 days later put the blame on Boehm for allowing the car to get so overcrowded. He testified from his hospital bed, having suffered two broken legs. He had been hired just a month before the accident, which was his first run in charge of a loaded car. Conductor J. D. Calhoun died in the crash. The privately owned Tacoma Railway and Power Co. was found guilty of criminal negligence in allowing such an inexperienced motorman to operate the streetcar and for failing to maintain the tracks and streetcar’s safety features. It faced bankruptcy from the flood of lawsuits by survivors and families of the dead. It eventually set up a $100,000 settlement fund that attorneys could either accept or risk getting nothing when the company went into receivership. The family and survivors accepted the deal. The Tacoma Railway and Power Company phased out the trestle, which was torn down in 1910 and never fully recovered.

The rise of cars and buses in the 1920s and 1930s dramatically cut into streetcar ridership. The last streetcars in Tacoma ran on June 11, 1938, with a celebratory last ride that ended with a dance at the Winthrop Hotel.

In a final twist of irony, the streetcar tracks were torn up and sold for scrap to Japan in 1939, which was suffering shortages of raw materials born from its military operations in Asia. Chinese Americans around the region protested the sale of Tacoma’s scrap steel with chants that the streetcar tracks would be returned as falling bombs. They were right, at least metaphorically.

Japan bombed Pearl Harbor two years later, prompting America to enter World War II.

Holter will talk about his book at Pacific Lutheran University’s Learning is for Forever program from 10:30 to 12:30 a.m. on Jan. 24 and from 7 to 9 p.m. on Feb. 28 at the Lakewood Historical Society’s meeting at St Mary’s Episcopal Church, 10630 Gravelly Lake Drive SW.