It is one of those “oh, yeah, why is that?” bits of local information about Tacoma that actually drew international attention and proved to be a landmark point in history that continues to shape the city to this day, 131 years later.

Tacoma is the only major city on the West Coast without a “Chinatown.” That truth might seem just an interesting factoid to strangers who have no knowledge of local history, and then maybe grows to be a mild curiosity if people learn that the transcontinental railroad was built thanks largely to Chinese workers before the turn of the last century.

Tacoma’s missing Chinatown becomes a full-on mystery of history when they then learn that Tacoma was the terminus for the Northern Pacific Railroad, making it a logical location for Chinese railroad workers to stay and build their lives once they laid the final tracks.

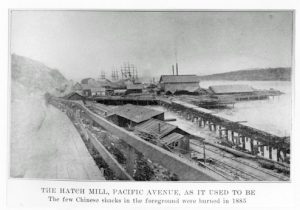

The fact is, they did – until a mob forced them out. Some 2,000 Chinese workers laid tracks from Kalama to Tacoma in the 1870s. They finished the work and used what meager wages they didn’t spend back to family members in China to build clusters of shacks and shops along Tacoma’s less-than-desirable waterfront since racial tensions and high property prices edged them out of both downtown and the city’s growing residential neighborhoods of white residents.

Racial tensions grew with the economic slump of 1873 and the rise of anti-Chinese laws up and down the West Coast. Cities and settlements with ties to the railroad saw riots and “random” attacks with the European immigrants and East Coast workers on one side and the Chinese workers on the other. Hundreds of Chinese workers were killed and thousands injured in clashes in the 1870s and 1880s. The white settlers blamed the Chinese for the lack of work and the low wages being offered for what scant jobs could be found.

Tacoma was no different in that respect. But what happened next made headlines around the world and became known as the “Tacoma Method,” a history lesson Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich would cite alongside America’s treatment of Native American’s as justification for his segregation and deportation of millions of people that then lead to the “Final Solution” the Jewish problem, known as the Holocaust, or the Shoah.

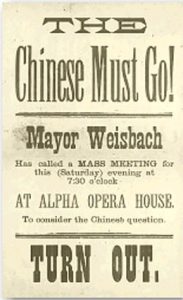

Leaders of the Knights of Labor began meeting with city and civic leaders in the late summer and early fall of 1885. Anti-Chinese posters and rallies began mushrooming up around the city, as chants and flyers boomed with “The Chinese Must Go!” and “Chinese? No! No! No!” Unlike the spontaneous fights in California and Oregon, Tacoma’s anti-Chinese movement was orchestrated from City Hall as well as the top brass of law enforcement playing key roles in what happened. Tacoma Mayor Jacob Robert Weisbach was among the ringleaders and openly called the Chinese “a curse” and a “filthy horde.”

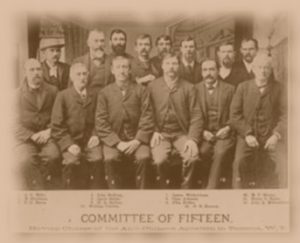

Pronouncements in the Tacoma Daily Ledger, on flyers and cries from the top of soapboxes as the fall air chilled were direct and brutal – the Chinese must leave or they will be removed. Businesses that hired Chinese workers were first forced to fire them and replace them with white or Native American employees. Harassment of Chinese residents became constant and increasingly brutal. Posters then set a date, November 3, 1885, after the “Committee of 15” was elected to administer the forced exile. Any remaining Chinese residents would be rounded up and forced out of town. Hundreds heeded the warning and left as fast as they could.

Some townspeople, among them Ezra Meeker, protested the rising tensions, but little was done to stop the calls for violence.

Knights of Labor and city officials planned through the night and early morning on how the banishment would work and set the plan into motion at 9:30 a.m. The Lister Foundry whistle blew with other steam whistles at mills around the city quickly following its lead. That was the signal. Hundreds of angry workers methodically walked through downtown, rounding up any Chinese residents they came across as they marched to the Chinese settlement and a rallying point at Seventh and Pacific Avenue. It was cold and rainy, a fact that only added to the misery.

The Chinese – some 200 young, old, men, women and children – had just minutes to gather their worldly possessions and leave or face beatings or death. They were marched to a train station in present-day Lakewood. Some sympathetic locals provided food and warm water for tea for the group that crowed into the station for the next outbound train – a 3:00 a.m. stack of cars heading to Portland. Two died of exposure to the cold weather as their homes burned to the ground. The train quickly filled, leaving the remaining members of this forced exodus to either wait for the next train or start walking south. Fearing violence, many opted for the latter – creating a forlorn march of stragglers that lasted for days.

“It was a sad spectacle,” Chinese businessman Lum May, who had lived in Tacoma longer than the German immigrant turned mayor who expelled him as a foreign newcomer, would later testify.

A similar, but less methodical Chinese expulsion occurred days later, a fact mocked as another reason Tacoma was superior to the Emerald City farther north.

Expecting to be cheered for their efficiency, the expulsion organizers were surprised that their horrors were vilified by politicians and newspaper editorials around the nation. Many perpetrators were arrested and sent to the federal facilities in Vancouver to face charges. They were given bail and returned to Tacoma to a welcome home celebration. Their trials were later transferred to Tacoma, where the charges were later dropped.

The United States government would later pay the Chinese government only $424,000 for all damages during riots and expulsions along the West Coast. Tacoma didn’t have a noticeable number of Chinese residents until after World War II, some three generations after the expulsion.

It wasn’t until 108 years after the “Tacoma Method” occurred that city officials took steps to make amends. That year, Tacoma City Councilmembers formally apologized for the actions of their predecessors and formed a committee that became the Reconciliation Foundation to “promote peace and harmony in our multicultural community.”

That effort culminated in the construction of the Chinese Reconciliation Park along Schuster Parkway, which opened in 2010 with future phases gathering funding.